Colaboración del C. de N. Edgardo Loret de Mola

Responsable de la edición: Rosario Yika Uribe

Fuente: Cinco

siglos del destino marítimo del Perú, de Esperanza Navarro Pantac:

Instituto de Estudios Histórico-Marítimos del Perú, 2016

Efemérides Navales de Hoy 31 diciembre

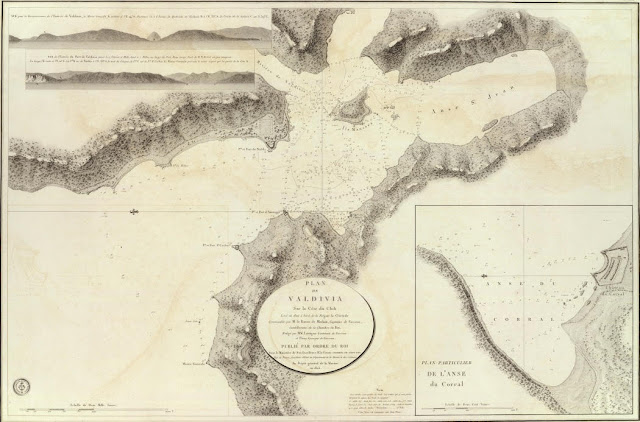

31 de diciembre 1644: Zarpa del Callao rumbo al sur una escuadra de 17 barcos, comandada por Antonio de Toledo, hijo del virrey marqués de Mancera para combatir a la flota holandesa de Brouwer en los mares de Chile (Valdivia). (Hendrik Brouwer había fallecido en Valdivia y la flota holandesa ya se había retirado cuando llegó la flota procedente del Callao)

31 de diciembre 1856: En el marco de la revolución de Vivanco, la Apurímac, Loa y el transporte Tumbes son vistos en la rada del Callao al ponerse el sol. Los buques rebeldes necesitan víveres. La goleta Izcuchaca debía conseguir agua fresca y dar encuentro a la Apurímac en la isla San Lorenzo.

1 de diciembre 1864: El capitán de corbeta Juan Pardo de Zela asume la comandancia de los nuevos buques América y Unión. El mando de la Unión es confiado al teniente primero Miguel Grau. (Como podemos apreciar en el extracto del artículo abajo, los dos buques fueron inicialmente construídos para la Marina Confederada durante la Guerra Civil en EEUU, pero la diplomacia de

los Estados Unidos logró impedir que fueran entregados y nos fueron vendidos. Sus dos gemelos fueron vendidos a la Marina de Prusia - que fue el embrión del cual nació la Marina Alemana - donde tomaron el nombre de Augusta y Victoria)

The Confederate agent Bulloch extended his ambitions when he contracted with Birkenhead shipbuilders, Laird and Sons, to construct two turreted ironclad rams. Bulloch based the rams upon the ideas of Capt. Cowper Coles of the Royal Navy, an outspoken British ironclad designer. They were impressive ships displacing 1,423 tons (light) and were 224.5 feet long. Their iron hulls had ram bows supporting two turrets carrying 220-pounder Armstrong guns; lighter guns were mounted on raised forecastles and quarterdecks. Bark sailing rigs gave them range; powerful twin-screw engines combined with ram bows gave them ability to fight the most imposing Union ships.

But the intended use of the rams could not be hidden or misdirected. Due to their ram bows, the ships were dangerous weapons platforms even before guns were mounted. In locations around Europe, Union consuls gathered depositions and other evidence sufficient to prove the rams' connection with the Confederate government. The persistent Liverpool consul, Thomas Haines Dudley, dogged Bulloch, employing private detectives, sympathetic sea captains, knowledgeable attorneys, and Confederate turncoats. He obtained copies of Confederate correspondence and internal Laird documents to gain knowledge of Bulloch's every move. The London consul, Freeman H. Morse, managed to induce a young London mechanic to get a job in the Laird shipyards with a promise of a recommendation to a U.S. shipbuilder. (The boy's mother found out and stopped the spying by threatening to expose him and the U.S. government's role in his activities.) In London, at the Court of St. James, Minister Adams once again ably presented Dudley's evidence and explained the U.S. government's view that release of the ironclad rams might be considered an act of war.

From Washington, Secretary Seward coordinated the action by mail and telegraph to stop the rams' delivery. Both rams were seized before completion to prevent them from slipping out of the country. Even a last-minute sham sale, ostensibly to a French company for delivery to Egypt, failed to free the two ships for the south. Caught in an awkward gap between domestic law and foreign policy, the British Crown ultimately bought the Laird rams and commissioned them HMS Scorpion and HMS Wivern.Brilliant cooperation between the three main branches of the State Department had prevented two dangerous warships from reaching the Confederate navy.

The British difficulty in maintaining strict neutrality had its roots in a conflict between two principles of law. Under the precepts of international law, neutral Great Britain had an obligation to prevent the building and outfitting of armed warships for any belligerent in its ports. The critical point was that the wording of the law and accepted international practice to that time prohibited sales of armed vessels only. The tenet of domestic law that held that a defendant is "innocent until proven guilty" allowed secretly built Confederate cruisers to be dispatched from British ports because positive proof of the cruiser's destination was nearly impossible to ascertain and arming took place outside British jurisdiction. Following the commissioning of Florida and Alabama, Great Britain was forced to prevent the departure of other vessels merely on justifiable suspicion that they were violating British domestic law.

Bulloch was disappointed by the loss of the Laird rams but had already expanded his operations beyond Great Britain. Negotiations with the French government produced a conditional agreement to provide four modern wood and iron composite steam clipper corvettes for long-distance cruising. These screw corvettes would have been the equal of any U.S. Navy cruisers. Further negotiations allowed contracts for two more powerful ironclad rams. These shallow-draft ironclad wooden ships were designed with a brig sailing rig and twin-screw steam auxiliary propulsion. With the screw corvettes they could present a dangerous challenge to the Union navy on the high seas, potentially capable of overwhelming smaller squadrons on individual blockading stations.

All six ships were contracted through Lucien Arman, a shipbuilder with a seat in the French legislature and strong political connections to the Emperor Louis Napoleon III. They were built in the yards of Arman in Bordeaux and, through engine-builder and fellow legislator M. Voruz, at the yards of Jollett & Babin and Dubigeon Brothers in Nantes. The sale was understood to have been approved by the emperor and permitted by the minister of the navy. The ostensible purpose was to start a steam packet line between San Francisco and Japan and China. The armament was said to enable them to fight off pirate attacks in eastern waters and to allow potential sale to the Japanese or Chinese governments.

But Consul General John Bigelow in Paris had been preparing to ward off any shipbuilding efforts for the Confederacy in France. He had gathered rumors and credited reports from other consuls that Southern agents had contacted French shipbuilders. But Bigelow had not expected the intelligence windfall that walked into his consular office on September 10, 1863. The man, a disloyal senior shipyard employee named Trémont, offered proof in the form of incriminating documents and assurance that his information would be sufficient to force the arrest of the ships under French law. Called "Mr. X" by Bigelow, Trémont asked for twenty thousand francs, a considerable sum of money, if his material should stop the ships from reaching the Confederates. Trémont delivered twenty-one documents that proved not only that the contract was for the Confederate navy but that it was approved by the French government.

Bigelow acted quickly. He delivered the documents to U.S. Minister to France William L. Dayton. Dayton and Seward used the same approach taken with Great Britain, namely to present as full a public case as possible proving un-neutral behavior. They also subtly threatened the French adventure to install Maximilian as ruler of Mexico and to delay the lucrative French government tobacco shipment from Virginia. French Foreign Affairs Minister Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys perceived the threat, and the danger of growing Northern sentiment against France, and acted to force his emperor and country back toward a neutral posture. He forced the shipbuilders to sell all six vessels to governments then at peace. Two corvettes were sold to Peru (América y Unión); two corvettes (Augusta y Victoria) and a ram were sold to Prussia; and one ram was sold to Sweden, or so the French government believed. The wily Arman had sold the ironclad to a Swedish banker, who was to sell it to Denmark. But when the Danes refused the ship, Arman was able to sell it back to the Confederacy. It was delayed so much by storms and an unwilling crew that the ironclad, commissioned CSS Stonewall, never played a part in the war.

But the intended use of the rams could not be hidden or misdirected. Due to their ram bows, the ships were dangerous weapons platforms even before guns were mounted. In locations around Europe, Union consuls gathered depositions and other evidence sufficient to prove the rams' connection with the Confederate government. The persistent Liverpool consul, Thomas Haines Dudley, dogged Bulloch, employing private detectives, sympathetic sea captains, knowledgeable attorneys, and Confederate turncoats. He obtained copies of Confederate correspondence and internal Laird documents to gain knowledge of Bulloch's every move. The London consul, Freeman H. Morse, managed to induce a young London mechanic to get a job in the Laird shipyards with a promise of a recommendation to a U.S. shipbuilder. (The boy's mother found out and stopped the spying by threatening to expose him and the U.S. government's role in his activities.) In London, at the Court of St. James, Minister Adams once again ably presented Dudley's evidence and explained the U.S. government's view that release of the ironclad rams might be considered an act of war.

From Washington, Secretary Seward coordinated the action by mail and telegraph to stop the rams' delivery. Both rams were seized before completion to prevent them from slipping out of the country. Even a last-minute sham sale, ostensibly to a French company for delivery to Egypt, failed to free the two ships for the south. Caught in an awkward gap between domestic law and foreign policy, the British Crown ultimately bought the Laird rams and commissioned them HMS Scorpion and HMS Wivern.Brilliant cooperation between the three main branches of the State Department had prevented two dangerous warships from reaching the Confederate navy.

The British difficulty in maintaining strict neutrality had its roots in a conflict between two principles of law. Under the precepts of international law, neutral Great Britain had an obligation to prevent the building and outfitting of armed warships for any belligerent in its ports. The critical point was that the wording of the law and accepted international practice to that time prohibited sales of armed vessels only. The tenet of domestic law that held that a defendant is "innocent until proven guilty" allowed secretly built Confederate cruisers to be dispatched from British ports because positive proof of the cruiser's destination was nearly impossible to ascertain and arming took place outside British jurisdiction. Following the commissioning of Florida and Alabama, Great Britain was forced to prevent the departure of other vessels merely on justifiable suspicion that they were violating British domestic law.

Bulloch was disappointed by the loss of the Laird rams but had already expanded his operations beyond Great Britain. Negotiations with the French government produced a conditional agreement to provide four modern wood and iron composite steam clipper corvettes for long-distance cruising. These screw corvettes would have been the equal of any U.S. Navy cruisers. Further negotiations allowed contracts for two more powerful ironclad rams. These shallow-draft ironclad wooden ships were designed with a brig sailing rig and twin-screw steam auxiliary propulsion. With the screw corvettes they could present a dangerous challenge to the Union navy on the high seas, potentially capable of overwhelming smaller squadrons on individual blockading stations.

All six ships were contracted through Lucien Arman, a shipbuilder with a seat in the French legislature and strong political connections to the Emperor Louis Napoleon III. They were built in the yards of Arman in Bordeaux and, through engine-builder and fellow legislator M. Voruz, at the yards of Jollett & Babin and Dubigeon Brothers in Nantes. The sale was understood to have been approved by the emperor and permitted by the minister of the navy. The ostensible purpose was to start a steam packet line between San Francisco and Japan and China. The armament was said to enable them to fight off pirate attacks in eastern waters and to allow potential sale to the Japanese or Chinese governments.

But Consul General John Bigelow in Paris had been preparing to ward off any shipbuilding efforts for the Confederacy in France. He had gathered rumors and credited reports from other consuls that Southern agents had contacted French shipbuilders. But Bigelow had not expected the intelligence windfall that walked into his consular office on September 10, 1863. The man, a disloyal senior shipyard employee named Trémont, offered proof in the form of incriminating documents and assurance that his information would be sufficient to force the arrest of the ships under French law. Called "Mr. X" by Bigelow, Trémont asked for twenty thousand francs, a considerable sum of money, if his material should stop the ships from reaching the Confederates. Trémont delivered twenty-one documents that proved not only that the contract was for the Confederate navy but that it was approved by the French government.

Bigelow acted quickly. He delivered the documents to U.S. Minister to France William L. Dayton. Dayton and Seward used the same approach taken with Great Britain, namely to present as full a public case as possible proving un-neutral behavior. They also subtly threatened the French adventure to install Maximilian as ruler of Mexico and to delay the lucrative French government tobacco shipment from Virginia. French Foreign Affairs Minister Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys perceived the threat, and the danger of growing Northern sentiment against France, and acted to force his emperor and country back toward a neutral posture. He forced the shipbuilders to sell all six vessels to governments then at peace. Two corvettes were sold to Peru (América y Unión); two corvettes (Augusta y Victoria) and a ram were sold to Prussia; and one ram was sold to Sweden, or so the French government believed. The wily Arman had sold the ironclad to a Swedish banker, who was to sell it to Denmark. But when the Danes refused the ship, Arman was able to sell it back to the Confederacy. It was delayed so much by storms and an unwilling crew that the ironclad, commissioned CSS Stonewall, never played a part in the war.

31 de diciembre 1885: Se establece la Mayoría de Órdenes del Departamento Marítimo del Callao.

31 de diciembre 1896: Se establece la Escuela Militar, Preparatoria y Naval, en el fundo Santa Sofía . (El Fundo Santa Sofía era propiedad de Augusto Dreyfus y la Escuela Naval estuvo ubicada en el local de la Escuela de Artes y Oficios, hoy Instituto Politécnico José Pardo)

31 de diciembre 1928: Se expide el Reglamento de Pensionistas de la Armada.

31 de diciembre 2015: El Decreto supremo N° 098-2015-PCM declara el año 2016 “Año de la consolidación del Mar de Grau”.